“OTHER TRANSACTION AUTHORITY” (OTA) AND ITS ASSOCIATED “OTHER TRANSACTIONS” (OTS)1 ARE EXPERIENCING A SURGE OF ACTIVITY,2 THANKS IN PART TO RECENT LEGISLATION.”

Certainly, OTA can be a valuable procurement tool if used correctly. In fact, recent efforts with the use of OTs have been overwhelmingly positive.

Unfortunately, there has also been an abundance of “hype” concerning OTA and OTs that could lead one to believe them to be a panacea for government contract ills—a “pill” that will result in fast and flawless procurements.3 Perhaps the most detrimental aspect of this “hype” is that it could lull members of Congress and senior executive branch leaders into thinking that serious procurement reform is no longer needed.

This article is not an explanation of what OTA and OTs are; rather, it is an explanation of what they are not. It seeks to clarify what OTs work well for, and to dispel the myths that have recently been cropping up due to the increased “hype” over OTA.

Exemplary of this “hype” is a recent Defense Acquisition University (DAU) video4 featuring an interview with Lauren Schmidt, the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx)5 Pathway Director. OTs are the contracting vehicle of choice for DIUx, and within the video, OTs are compared to conventional Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)–based contracts and are heralded as:

Let’s examine each of these categories in turn.

Certainly, OTA can be a valuable procurement tool if used correctly. In fact, recent efforts with the use of OTs have been overwhelmingly positive.

Unfortunately, there has also been an abundance of “hype” concerning OTA and OTs that could lead one to believe them to be a panacea for government contract ills—a “pill” that will result in fast and flawless procurements.3 Perhaps the most detrimental aspect of this “hype” is that it could lull members of Congress and senior executive branch leaders into thinking that serious procurement reform is no longer needed.

This article is not an explanation of what OTA and OTs are; rather, it is an explanation of what they are not. It seeks to clarify what OTs work well for, and to dispel the myths that have recently been cropping up due to the increased “hype” over OTA.

Exemplary of this “hype” is a recent Defense Acquisition University (DAU) video4 featuring an interview with Lauren Schmidt, the Defense Innovation Unit Experimental (DIUx)5 Pathway Director. OTs are the contracting vehicle of choice for DIUx, and within the video, OTs are compared to conventional Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR)–based contracts and are heralded as:

- Faster,

- More flexible, and

- More collaborative.

Let’s examine each of these categories in turn.

1. “FASTER”

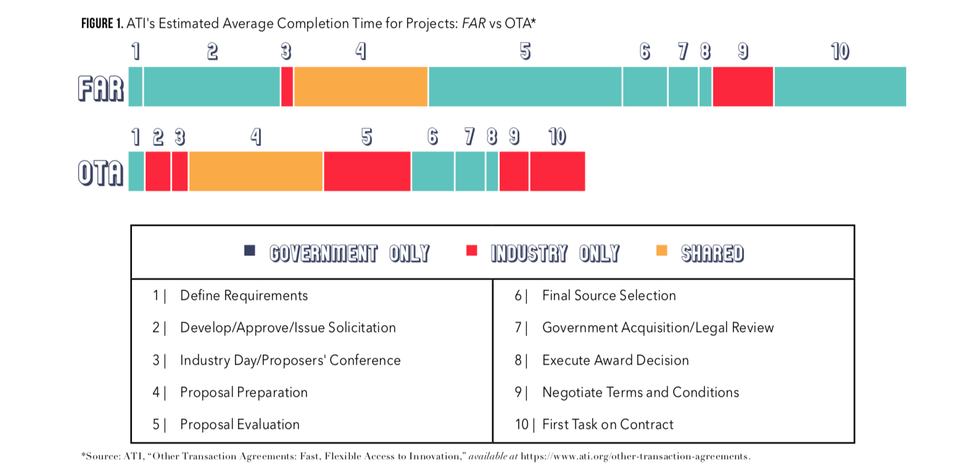

Perhaps the best documented explanation of why OTs are supposedly “faster” than conventional FAR-based contracts has been compiled by Advanced Technology International (ATI), a nonprofit specializing in collaborative research initiatives between industry and the U.S. federal government. FIGURE 1 below shows information compiled by ATI, which contrasts their estimates for the time a conventional FAR- based project contract takes versus an OTA-based project for the chronological components of the acquisition cycle.6

It is useful to examine those components of the acquisition cycle that ATI asserts can be more quickly accomplished using an OT to see if ATI’s assertions can withstand scrutiny. Specifically, the authors of this article contend that the following components are “suspect”:

Perhaps the best documented explanation of why OTs are supposedly “faster” than conventional FAR-based contracts has been compiled by Advanced Technology International (ATI), a nonprofit specializing in collaborative research initiatives between industry and the U.S. federal government. FIGURE 1 below shows information compiled by ATI, which contrasts their estimates for the time a conventional FAR- based project contract takes versus an OTA-based project for the chronological components of the acquisition cycle.6

It is useful to examine those components of the acquisition cycle that ATI asserts can be more quickly accomplished using an OT to see if ATI’s assertions can withstand scrutiny. Specifically, the authors of this article contend that the following components are “suspect”:

- “(2) Develop/Approve/Issue Solicitation”;

- “(5) Proposal Evaluation”;

- “(9) Negotiate Terms and Conditions”;

- “(10) First Task on Contract.”

DEVELOP/APPROVE/ISSUE SOLICITATION

ATI is probably correct in asserting that it takes longer for a conventional FAR procurement to complete the development, approval, and issuance of a solicitation than it takes with an OT. However, it does not have to be that way. There are examples to the contrary.7 Sadly, heads of contracting activities (HCAs) have grown accustomed to bureaucratic ways that stifle promptly developing, approving, and issuing a solicitation. However, this bureaucratic lethargy could be overcome with dynamic leadership at the HCA level.8

PROPOSAL EVALUATION

Academically, there is no cogent reason why a proposal for a conventional FAR procurement should take longer to evaluate than a proposal for an OT. The amount of time to perform an evaluation largely depends on the competency and availability of evaluators. Anecdotally, because of their higher visibility and more dynamic government team, OTs are able to attract more competent evaluators who are available to work on an expedited basis.

Another likely advantage for OTs is that they generally have more focused evaluation factors that are likely to be the actual discriminators for source selection. Although FAR 15.304 has long admonished tailoring the evaluation criteria to expeditiously discern the best proposal, all too often for conventional FAR acquisitions the evaluation criteria follow a rote format. If agencies used more focused evaluation factors for conventional FAR acquisitions, the balance in favor of OTs with respect to evaluation timelines would likely tip back the other way.

NEGOTIATE TERMS AND CONDITIONS

The ATI graphic would have the reader believe an OT takes approximately a third of the amount of time to negotiate compared to a conventional FAR contract. This assertion is not based in logic. Negotiation takes two parties. As a norm, the more there is to negotiate, the longer the negotiations are likely to take. As will be discussed, there is considerably more to negotiate for OTs than there is to negotiate for conventional FAR procurements.

A conventional FAR procurement contains numerous clauses—many of which are mandatory. Viewed pragmatically, these clauses are tantamount to being pre-agreed-to terms and conditions by the parties. To state the obvious, pre-agreed clauses generally take less time to negotiate. Consider, for example, the time that can be saved by not having to negotiate clauses such as a “disputes” clause, a “changes” clause, or a “termination for convenience” clause.

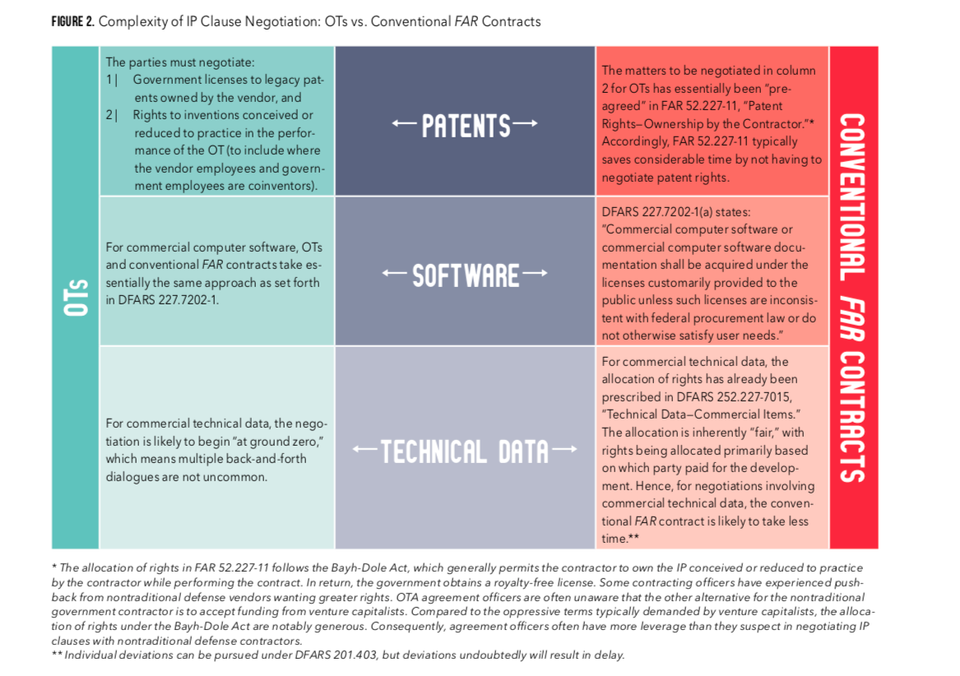

Intellectual property (IP) clauses are an excellent example of provisions that are susceptible to prolonged negotiations for OTs. DIUx has made clear that IP clauses are a major concern to the nontraditional defense contractors with whom DIUx seeks to do business. Accordingly, IP clauses are generally the focus of considerable attention when negotiating an OT for a prototype from a nontraditional defense contractor. FIGURE 2 on explains why it is likely to take significantly more time to negotiate IP clauses for an OT compared to negotiating IP clauses for a conventional FAR contract.

ATI is probably correct in asserting that it takes longer for a conventional FAR procurement to complete the development, approval, and issuance of a solicitation than it takes with an OT. However, it does not have to be that way. There are examples to the contrary.7 Sadly, heads of contracting activities (HCAs) have grown accustomed to bureaucratic ways that stifle promptly developing, approving, and issuing a solicitation. However, this bureaucratic lethargy could be overcome with dynamic leadership at the HCA level.8

PROPOSAL EVALUATION

Academically, there is no cogent reason why a proposal for a conventional FAR procurement should take longer to evaluate than a proposal for an OT. The amount of time to perform an evaluation largely depends on the competency and availability of evaluators. Anecdotally, because of their higher visibility and more dynamic government team, OTs are able to attract more competent evaluators who are available to work on an expedited basis.

Another likely advantage for OTs is that they generally have more focused evaluation factors that are likely to be the actual discriminators for source selection. Although FAR 15.304 has long admonished tailoring the evaluation criteria to expeditiously discern the best proposal, all too often for conventional FAR acquisitions the evaluation criteria follow a rote format. If agencies used more focused evaluation factors for conventional FAR acquisitions, the balance in favor of OTs with respect to evaluation timelines would likely tip back the other way.

NEGOTIATE TERMS AND CONDITIONS

The ATI graphic would have the reader believe an OT takes approximately a third of the amount of time to negotiate compared to a conventional FAR contract. This assertion is not based in logic. Negotiation takes two parties. As a norm, the more there is to negotiate, the longer the negotiations are likely to take. As will be discussed, there is considerably more to negotiate for OTs than there is to negotiate for conventional FAR procurements.

A conventional FAR procurement contains numerous clauses—many of which are mandatory. Viewed pragmatically, these clauses are tantamount to being pre-agreed-to terms and conditions by the parties. To state the obvious, pre-agreed clauses generally take less time to negotiate. Consider, for example, the time that can be saved by not having to negotiate clauses such as a “disputes” clause, a “changes” clause, or a “termination for convenience” clause.

Intellectual property (IP) clauses are an excellent example of provisions that are susceptible to prolonged negotiations for OTs. DIUx has made clear that IP clauses are a major concern to the nontraditional defense contractors with whom DIUx seeks to do business. Accordingly, IP clauses are generally the focus of considerable attention when negotiating an OT for a prototype from a nontraditional defense contractor. FIGURE 2 on explains why it is likely to take significantly more time to negotiate IP clauses for an OT compared to negotiating IP clauses for a conventional FAR contract.

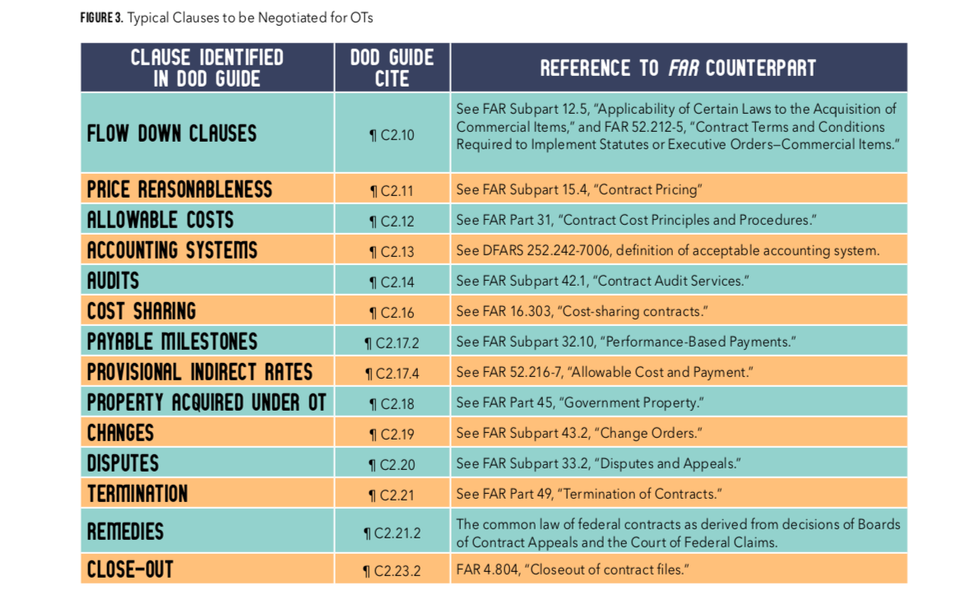

In addition to the IP clauses that are commonly negotiated for OTs, there are numerous other clauses that should be negotiated. Several such clauses were identified in the DOD Other Transactions Guide for Prototype Projects (January 2017).9 Listed in FIGURE 3 below are some of those clauses.

In summary, for the acquisition of a prototype, it logically would take significantly longer to negotiate the appropriate clauses for an OT than the appropriate clauses for a conventional FAR procurement. While ATI asserts that terms and conditions would be more quickly negotiated for OTs, this seems only possible if:

In summary, for the acquisition of a prototype, it logically would take significantly longer to negotiate the appropriate clauses for an OT than the appropriate clauses for a conventional FAR procurement. While ATI asserts that terms and conditions would be more quickly negotiated for OTs, this seems only possible if:

- Those negotiating OTs simply use the FAR clauses regarding IP, or

- The OTA agreements officers simply accept what industry wants without negotiation.

FIRST TASK ON CONTRACT

ATI would have us believe that it takes more than twice as long to place the first task on a conventional FAR contract than to place the order using an OT. Logic does not support such an assertion.

Although the term “on contract” is vague, for a conventional FAR contract, ATI is probably referring to the first task order for an indefinite-quantity contract under FAR 16.504. Orders under such contracts do not require any synopsis publications.10 Additionally, there are significant limita- tions on protesting such task orders.11 In short, the administrative step of issuing the first task is essentially the same for both the FAR-based indefinite-quantity contract and the OT.

Although ATI may have had anecdotal experience to support their assertion that it takes twice as long for the first task to

be issued on a conventional FAR contract compared to an OT, the only logical explanation is bureaucratic ineptness. In all probability, when the mystic of OTs wears off, OTs will similarly be plagued with similar delays.

2. “MORE FLEXIBLE”

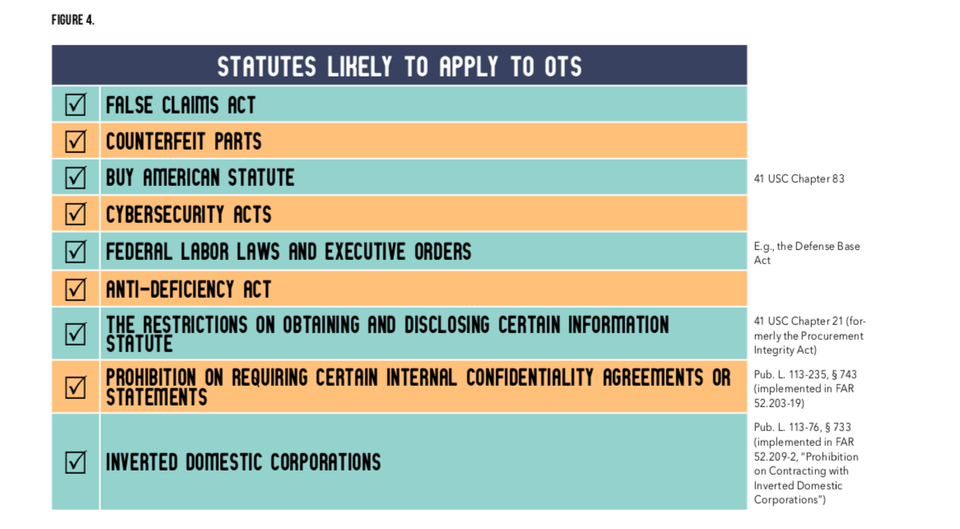

Ms. Schmidt is on firm ground in asserting that OTs are “more flexible” than conventional FAR contracts.12 However, hype creeps in when she states: “Because all of the terms and conditions of OTs are negotiable, we can negotiate directly with those companies and design an OT that works best for all parties.”13 The truth is that there are numerous terms and conditions obligated by law or Executive Order which still must be included in OTs:

OTs generally are not required to comply with laws that are limited in applicability solely to procurement contracts, such as the Truthful Cost or Pricing Data [statute]... However, if a particular requirement is not tied to the type of instrument used, it generally would apply to an OT—for example, fiscal and property laws generally would apply to OTs for prototype projects.14

FIGURE 4 contains a partial list of statutes that are highly probable to be binding on OTs.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has accurately identified the underlying problem:

According to company representatives that we spoke to, DOD’s acquisition environment presents unique challenges to non-traditional companies that they otherwise do not experience in the private industry. The acquisition environment is driven by laws that provide transparency and fairness, regulations that promote specific socio-economic goals, and DOD’s approach for implementing those laws and regulations. For the most part, the selected 12 companies we spoke with expressed frustration with the complexity of DOD’s acquisition process; the time, cost, and risk associated with competing for and executing a contract; and interacting with DOD’s contracting workforce.15

ATI would have us believe that it takes more than twice as long to place the first task on a conventional FAR contract than to place the order using an OT. Logic does not support such an assertion.

Although the term “on contract” is vague, for a conventional FAR contract, ATI is probably referring to the first task order for an indefinite-quantity contract under FAR 16.504. Orders under such contracts do not require any synopsis publications.10 Additionally, there are significant limita- tions on protesting such task orders.11 In short, the administrative step of issuing the first task is essentially the same for both the FAR-based indefinite-quantity contract and the OT.

Although ATI may have had anecdotal experience to support their assertion that it takes twice as long for the first task to

be issued on a conventional FAR contract compared to an OT, the only logical explanation is bureaucratic ineptness. In all probability, when the mystic of OTs wears off, OTs will similarly be plagued with similar delays.

2. “MORE FLEXIBLE”

Ms. Schmidt is on firm ground in asserting that OTs are “more flexible” than conventional FAR contracts.12 However, hype creeps in when she states: “Because all of the terms and conditions of OTs are negotiable, we can negotiate directly with those companies and design an OT that works best for all parties.”13 The truth is that there are numerous terms and conditions obligated by law or Executive Order which still must be included in OTs:

OTs generally are not required to comply with laws that are limited in applicability solely to procurement contracts, such as the Truthful Cost or Pricing Data [statute]... However, if a particular requirement is not tied to the type of instrument used, it generally would apply to an OT—for example, fiscal and property laws generally would apply to OTs for prototype projects.14

FIGURE 4 contains a partial list of statutes that are highly probable to be binding on OTs.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) has accurately identified the underlying problem:

According to company representatives that we spoke to, DOD’s acquisition environment presents unique challenges to non-traditional companies that they otherwise do not experience in the private industry. The acquisition environment is driven by laws that provide transparency and fairness, regulations that promote specific socio-economic goals, and DOD’s approach for implementing those laws and regulations. For the most part, the selected 12 companies we spoke with expressed frustration with the complexity of DOD’s acquisition process; the time, cost, and risk associated with competing for and executing a contract; and interacting with DOD’s contracting workforce.15

3. “MORE COLLABORATIVE”

Industry would probably confirm that the government is more collaborative in pursuing OTs than in pursuing conventional FAR procurements—but, it does not have to be that way. The FAR also provides the flexibility to contracting officers to be more collaborative if they simply choose to do so. For example, the FAR states:

The government must not hesitate to communicate with the commercial sector as early as possible in the acquisition cycle to help the government determine the capabilities avail- able in the commercial marketplace.18

Sadly, conventional FAR acquisitions are typically undertaken in a culture where collaboration is not encouraged. This harmful culture has been addressed by the Office of Federal Procurement Policy.

In the private sector, when one party ex- presses an interest in using the technology of another party, the parties typically sign a non- disclosure agreement (NDA) before the party with the technology shares trade secrets. Although nontraditional defense contractors would prefer to follow that practice when dealing with the government, rarely does the government cooperate in this regard. Nevertheless, there is no reason why government personnel cannot sign NDAs.19

In summary, the reason why conventional FAR contracts are less collaborative is not because the FAR prohibits such collaboration. Instead, the reason is because contracting officers generally are unwilling to conduct the procurement in a more collaborative way. Thus, hyping OTs as “more collaborative” is simply that—hype.

EXPLAINING DIUX’S SUCCESS WITH OTS

DIUx’s successes are real, and DIUx should be commended for its achievements. However, based on the previous discussion that conventional FAR procurements offer essentially the same opportunities as OTs for fast, flexible, and collaborative procurements, DIUx’s success probably does not lie exclusively with its use of OTs.

Instead, perhaps the foremost reason is that DIUx has attracted highly competent acquisition professionals. A possible secondary reason is a phenomenon called the “Hawthorne effect” or the “observer effect.” In the field of psychology, the Hawthorne effect occurs when a group of people under observation changes its behavior to please the observers rather than reacting to the variables the researchers have injected into the experiment. Stated differently, the highly competent staff at DIUx were probably even more conscientious and hard- working in performing their duties because they knew their experimental unit was under close scrutiny and evaluation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, OTA and OTs are experiencing a revitalization. OTs are a valuable acquisition tool if used correctly; however, they are not a panacea for all ills. There is reason for concern that the “hype” which OTs have recently attracted could influence Congress and high-level executive branch officials into halting further improvement upon the convention federal acquisition process.

Frank Kendall, former Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics), aptly described the current situation involving OTA and OTs:

After decades of searching for some new form of acquisition magic, it may be time to accept that the basics of fostering professionalism in both government and industry, developing sound requirements through close operator and acquirer cooperation, strong well-crafted incentives, and disciplined attention to detail...rep- resents the best route to improving defense acquisition.20

Put in the proper perspective, OTs have their uses, and they are effective, but “faster,” “more flexible,” and “more collaborative” procurements are best achieved when the acquisition is overseen by highly qualified acquisition professionals. If members of Congress and senior executive branch leaders believe an inexperienced procurement workforce can achieve a successful prototype acquisition simply through the use of an OT, then they have bought into “some new form of acquisition magic.” CM

Industry would probably confirm that the government is more collaborative in pursuing OTs than in pursuing conventional FAR procurements—but, it does not have to be that way. The FAR also provides the flexibility to contracting officers to be more collaborative if they simply choose to do so. For example, the FAR states:

The government must not hesitate to communicate with the commercial sector as early as possible in the acquisition cycle to help the government determine the capabilities avail- able in the commercial marketplace.18

Sadly, conventional FAR acquisitions are typically undertaken in a culture where collaboration is not encouraged. This harmful culture has been addressed by the Office of Federal Procurement Policy.

In the private sector, when one party ex- presses an interest in using the technology of another party, the parties typically sign a non- disclosure agreement (NDA) before the party with the technology shares trade secrets. Although nontraditional defense contractors would prefer to follow that practice when dealing with the government, rarely does the government cooperate in this regard. Nevertheless, there is no reason why government personnel cannot sign NDAs.19

In summary, the reason why conventional FAR contracts are less collaborative is not because the FAR prohibits such collaboration. Instead, the reason is because contracting officers generally are unwilling to conduct the procurement in a more collaborative way. Thus, hyping OTs as “more collaborative” is simply that—hype.

EXPLAINING DIUX’S SUCCESS WITH OTS

DIUx’s successes are real, and DIUx should be commended for its achievements. However, based on the previous discussion that conventional FAR procurements offer essentially the same opportunities as OTs for fast, flexible, and collaborative procurements, DIUx’s success probably does not lie exclusively with its use of OTs.

Instead, perhaps the foremost reason is that DIUx has attracted highly competent acquisition professionals. A possible secondary reason is a phenomenon called the “Hawthorne effect” or the “observer effect.” In the field of psychology, the Hawthorne effect occurs when a group of people under observation changes its behavior to please the observers rather than reacting to the variables the researchers have injected into the experiment. Stated differently, the highly competent staff at DIUx were probably even more conscientious and hard- working in performing their duties because they knew their experimental unit was under close scrutiny and evaluation.

CONCLUSION

In summary, OTA and OTs are experiencing a revitalization. OTs are a valuable acquisition tool if used correctly; however, they are not a panacea for all ills. There is reason for concern that the “hype” which OTs have recently attracted could influence Congress and high-level executive branch officials into halting further improvement upon the convention federal acquisition process.

Frank Kendall, former Under Secretary of Defense (Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics), aptly described the current situation involving OTA and OTs:

After decades of searching for some new form of acquisition magic, it may be time to accept that the basics of fostering professionalism in both government and industry, developing sound requirements through close operator and acquirer cooperation, strong well-crafted incentives, and disciplined attention to detail...rep- resents the best route to improving defense acquisition.20

Put in the proper perspective, OTs have their uses, and they are effective, but “faster,” “more flexible,” and “more collaborative” procurements are best achieved when the acquisition is overseen by highly qualified acquisition professionals. If members of Congress and senior executive branch leaders believe an inexperienced procurement workforce can achieve a successful prototype acquisition simply through the use of an OT, then they have bought into “some new form of acquisition magic.” CM

ENDNOTES

1. Note: In current usage, the acronym “OTA” is often used to refer to both “other transaction authority” and “other transaction agreement” interchangeably. For clarity and consistency within this article, “OTA” shall refer to “other transaction authority” and “OT” shall refer to “other transaction”/“other transaction agreement.”

2. See, e.g., Angela Styles, “Other Transaction Authority—Big Rewards, Risks,” National Defense magazine (September 27, 2018), available at http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/ articles/2018/9/27/ethics-corner-other- transaction-authority---big-rewards-risks (stating “the Defense Department’s use of other transaction authority has increased 100-fold, attracting both traditional and nontraditional contractors to the table”); and Scott Maucione, “OTA Contracts are the Cool New Thing in DOD Acquisition,” Federal News Network (October 19, 2017), available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/ acquisition/2017/10/ota-contracts-are-the-new- cool-thing-in-dod-acquisition (stating “[o]ther transaction authority contracts seem to be the hip new thing in defense acquisition circles”).

3. See Frank Kendall, “The New Other Transactions Authority Guide: Helpful, But Not Enough,” Forbes (January 3, 2019), available at https://www.forbes. com/sites/frankkendall/2019/01/03/the-new- other-transactions-authority-guide-helpful-but- not-enough/#526c236c41cf (stating “[t]here is a perception in some quarters that OTAs are a magic wand that can eliminate the difficulties of doing business with the government”).

4. “DIUx: Pathways to Commercial Innovation and OTAs,” available at https://media.dau.mil/media/DIUxA+Pathways+to+Commercial+Innovation+an d+Other+Transaction+Authority+%28+OTAs%29/ 1_7zjckbnq.

5. DIUx was founded by then Secretary of Defense Ash Carter to help the Department of Defense more quickly tap into emerging commercial technologies.

6. ATI, “Other Transaction Agreements: Fast, Flexible Access to Innovation,” available at https://www.ati.org/other-transaction-agreements.

7. One example is the GBU-28 Bunker Buster that was that went from concept to deployment in the Gulf War in record time. (See Federation of Ameri- can Scientists, Military Analysis Network, “Guided Bomb Unit-28 (GBU-28) BLU-113 Penetrator, available at https://fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/smart/ gbu-28.htm.)

8. A potential obstacle for prototypes acquired under conventional FAR procedures is the FAR 5.203(e) requirement of at least a 45-day response time for vendors to submit proposals commencing with the release of the solicitation.

9. The January 2017 version has since been rescinded and replaced by a terser DOD Guide. (See https://aaf.dau.mil/ot-guide/.) However, nothing in the more current DOD Guide contradicts those clauses/topics identified in the July 2017 Guide as appropriate for addressing in OTs.

10. FAR 16.505(a)(1).

11. According to FAR 16.505(a)(10)(i): “No protest under subpart 33.1 is authorized in connection with the issuance or proposed issuance of an order under a task-order contract or delivery- order contract, except....[a] protest on the grounds that the order increases the scope, period, or maximum value of the contract; or.... [f]or agencies other than DOD, NASA, and the Coast Guard, a protest of an order valued in excess of $10 million....or [f]or DOD, NASA, or the Coast Guard, a protest of an order valued in excess of $25 million....”

12. A frequently cited example of greater flexibility is the statutory relief granted to OTs concerning the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA; 10 USC 2371(i)). Specifically, OTA excludes from FOIA disclosure: “information [that] was submitted to [DOD] in a competitive or noncompetitive process having the potential for resulting in an award, to the party submitting the information.” However, this statutory relief is unnecessary. There is essentially identical protection against FOIA requests already within the FAR. As FAR 52.203(b)(2)(ii) states: “The government, to the extent permitted by law and regulation, will safeguard and treat information obtained pursuant to the contractor’s disclosure as confidential where the information has been marked ‘confidential’ or ‘proprietary’ by the company. To the extent permitted by law and regulation, such information will not be released by the government to the public pursuant to a [FOIA] request.”

13. Lauren Schmidt, as quoted within “DIUx: Pathways to Commercial Innovation and OTAs,” see note 4.

14. DOD Other Transactions Guide for Prototype Projects (January 2017), see note 9, at ¶ C.2.7.2. (Elsewhere, the DOD Guide states: “However, in negotiating these clauses, the agreements officer must consider other laws that affect the government’s use and handling of intellectual property, such as the Trade Secrets Act; the Economic Espionage Act; the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA); the Privacy Act; and the Lanham Act.” (Ibid., at ¶ C2.3.1.1.)

15. GAO, “Military Acquisitions: DOD Is Taking Steps to Address Challenges Faced by Certain Companies,” GAO-17-644 (July 2017): 8 (emphasis added).

16. FAR 1.101(b)(1).

17. GAO Report, “Federal Acquisitions: Congress and the Executive Branch Have Taken Steps to Address Key Issues, but Challenges Endure” (September 2018): 37.

18. FAR 1.102-2(a)(4).

19. A sample NDA can be found in DFARS 227.7103-7, “Use of Non-Disclosure Agreements.” (See also OFPP’s “Myth-Busting Memo 2,” Misperception #5 (May 7, 2012), which states: “In cases where a vendor is concerned that existing protections are insufficient and engaging in pre-solicitation communication will be beneficial, agencies should consider the use of appropriate non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) to ensure that proprietary information will be kept from potential competitors.”

20. Frank Kendall, “Analysis: Five Myths About Pentagon Weapons Programs,” Government Executive (March 21, 2018), available at http://www.govexec. com/contracting/2018/03/analysis-five-myths- about-pentagon-weapons-programs/146816/ (emphasis added).

1. Note: In current usage, the acronym “OTA” is often used to refer to both “other transaction authority” and “other transaction agreement” interchangeably. For clarity and consistency within this article, “OTA” shall refer to “other transaction authority” and “OT” shall refer to “other transaction”/“other transaction agreement.”

2. See, e.g., Angela Styles, “Other Transaction Authority—Big Rewards, Risks,” National Defense magazine (September 27, 2018), available at http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/ articles/2018/9/27/ethics-corner-other- transaction-authority---big-rewards-risks (stating “the Defense Department’s use of other transaction authority has increased 100-fold, attracting both traditional and nontraditional contractors to the table”); and Scott Maucione, “OTA Contracts are the Cool New Thing in DOD Acquisition,” Federal News Network (October 19, 2017), available at https://federalnewsnetwork.com/ acquisition/2017/10/ota-contracts-are-the-new- cool-thing-in-dod-acquisition (stating “[o]ther transaction authority contracts seem to be the hip new thing in defense acquisition circles”).

3. See Frank Kendall, “The New Other Transactions Authority Guide: Helpful, But Not Enough,” Forbes (January 3, 2019), available at https://www.forbes. com/sites/frankkendall/2019/01/03/the-new- other-transactions-authority-guide-helpful-but- not-enough/#526c236c41cf (stating “[t]here is a perception in some quarters that OTAs are a magic wand that can eliminate the difficulties of doing business with the government”).

4. “DIUx: Pathways to Commercial Innovation and OTAs,” available at https://media.dau.mil/media/DIUxA+Pathways+to+Commercial+Innovation+an d+Other+Transaction+Authority+%28+OTAs%29/ 1_7zjckbnq.

5. DIUx was founded by then Secretary of Defense Ash Carter to help the Department of Defense more quickly tap into emerging commercial technologies.

6. ATI, “Other Transaction Agreements: Fast, Flexible Access to Innovation,” available at https://www.ati.org/other-transaction-agreements.

7. One example is the GBU-28 Bunker Buster that was that went from concept to deployment in the Gulf War in record time. (See Federation of Ameri- can Scientists, Military Analysis Network, “Guided Bomb Unit-28 (GBU-28) BLU-113 Penetrator, available at https://fas.org/man/dod-101/sys/smart/ gbu-28.htm.)

8. A potential obstacle for prototypes acquired under conventional FAR procedures is the FAR 5.203(e) requirement of at least a 45-day response time for vendors to submit proposals commencing with the release of the solicitation.

9. The January 2017 version has since been rescinded and replaced by a terser DOD Guide. (See https://aaf.dau.mil/ot-guide/.) However, nothing in the more current DOD Guide contradicts those clauses/topics identified in the July 2017 Guide as appropriate for addressing in OTs.

10. FAR 16.505(a)(1).

11. According to FAR 16.505(a)(10)(i): “No protest under subpart 33.1 is authorized in connection with the issuance or proposed issuance of an order under a task-order contract or delivery- order contract, except....[a] protest on the grounds that the order increases the scope, period, or maximum value of the contract; or.... [f]or agencies other than DOD, NASA, and the Coast Guard, a protest of an order valued in excess of $10 million....or [f]or DOD, NASA, or the Coast Guard, a protest of an order valued in excess of $25 million....”

12. A frequently cited example of greater flexibility is the statutory relief granted to OTs concerning the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA; 10 USC 2371(i)). Specifically, OTA excludes from FOIA disclosure: “information [that] was submitted to [DOD] in a competitive or noncompetitive process having the potential for resulting in an award, to the party submitting the information.” However, this statutory relief is unnecessary. There is essentially identical protection against FOIA requests already within the FAR. As FAR 52.203(b)(2)(ii) states: “The government, to the extent permitted by law and regulation, will safeguard and treat information obtained pursuant to the contractor’s disclosure as confidential where the information has been marked ‘confidential’ or ‘proprietary’ by the company. To the extent permitted by law and regulation, such information will not be released by the government to the public pursuant to a [FOIA] request.”

13. Lauren Schmidt, as quoted within “DIUx: Pathways to Commercial Innovation and OTAs,” see note 4.

14. DOD Other Transactions Guide for Prototype Projects (January 2017), see note 9, at ¶ C.2.7.2. (Elsewhere, the DOD Guide states: “However, in negotiating these clauses, the agreements officer must consider other laws that affect the government’s use and handling of intellectual property, such as the Trade Secrets Act; the Economic Espionage Act; the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA); the Privacy Act; and the Lanham Act.” (Ibid., at ¶ C2.3.1.1.)

15. GAO, “Military Acquisitions: DOD Is Taking Steps to Address Challenges Faced by Certain Companies,” GAO-17-644 (July 2017): 8 (emphasis added).

16. FAR 1.101(b)(1).

17. GAO Report, “Federal Acquisitions: Congress and the Executive Branch Have Taken Steps to Address Key Issues, but Challenges Endure” (September 2018): 37.

18. FAR 1.102-2(a)(4).

19. A sample NDA can be found in DFARS 227.7103-7, “Use of Non-Disclosure Agreements.” (See also OFPP’s “Myth-Busting Memo 2,” Misperception #5 (May 7, 2012), which states: “In cases where a vendor is concerned that existing protections are insufficient and engaging in pre-solicitation communication will be beneficial, agencies should consider the use of appropriate non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) to ensure that proprietary information will be kept from potential competitors.”

20. Frank Kendall, “Analysis: Five Myths About Pentagon Weapons Programs,” Government Executive (March 21, 2018), available at http://www.govexec. com/contracting/2018/03/analysis-five-myths- about-pentagon-weapons-programs/146816/ (emphasis added).

JERRY GABIG, FELLOW

RICH RALEIGH

- Practices law in Huntsville, Alabama

- Co-chair, Wilmer & Lee Government Contracts Practice Group

- Cofounder, Alabama State Bar Government Contracts Section

- Regularly appears in GAO and COFC cases involving government contract disputes

- Retired U.S. Air Force JAG officer

RICH RALEIGH

- Practices law in Huntsville, Alabama

- Co-chair, Wilmer & Lee Government

- Contracts Practice Group

- Cofounder, Alabama State Bar Government Contracts Section

- Regularly appears in GAO and COFC cases involving government contract disputes

- Member, Public Contracts Law Section of the American Bar Association (ABA)

- Serves in the ABA House of Delegates Past President, Alabama State Bar